A book review by BPL team member, Christian.

While going through some literary articles recently, I stumbled upon one by The Japan Times that discusses the idea of the new Japanese literary golden age. This article debates the merits of whether Japan is experiencing a new literary golden age and how Anglo-saxon translations funnel that to a Western audience. While the outcome of a contemporary literary Golden Age for Japan is left open-ended, it is certain that the voices of women authorship has significantly grown. However, an aspect of it, as mentioned previously, is determined by translation. For instance, one of the books shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2020, The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa, was initially published in Japan in 1994. A lot of writers that are defining the contemporary Japanese literary landscape have yet to make their impact in the Western world, but with the recent translations of authors such as Hiromi Kawakami, Hiroko Oyamada, Yukiko Motoya, and many more, that is slowly changing.

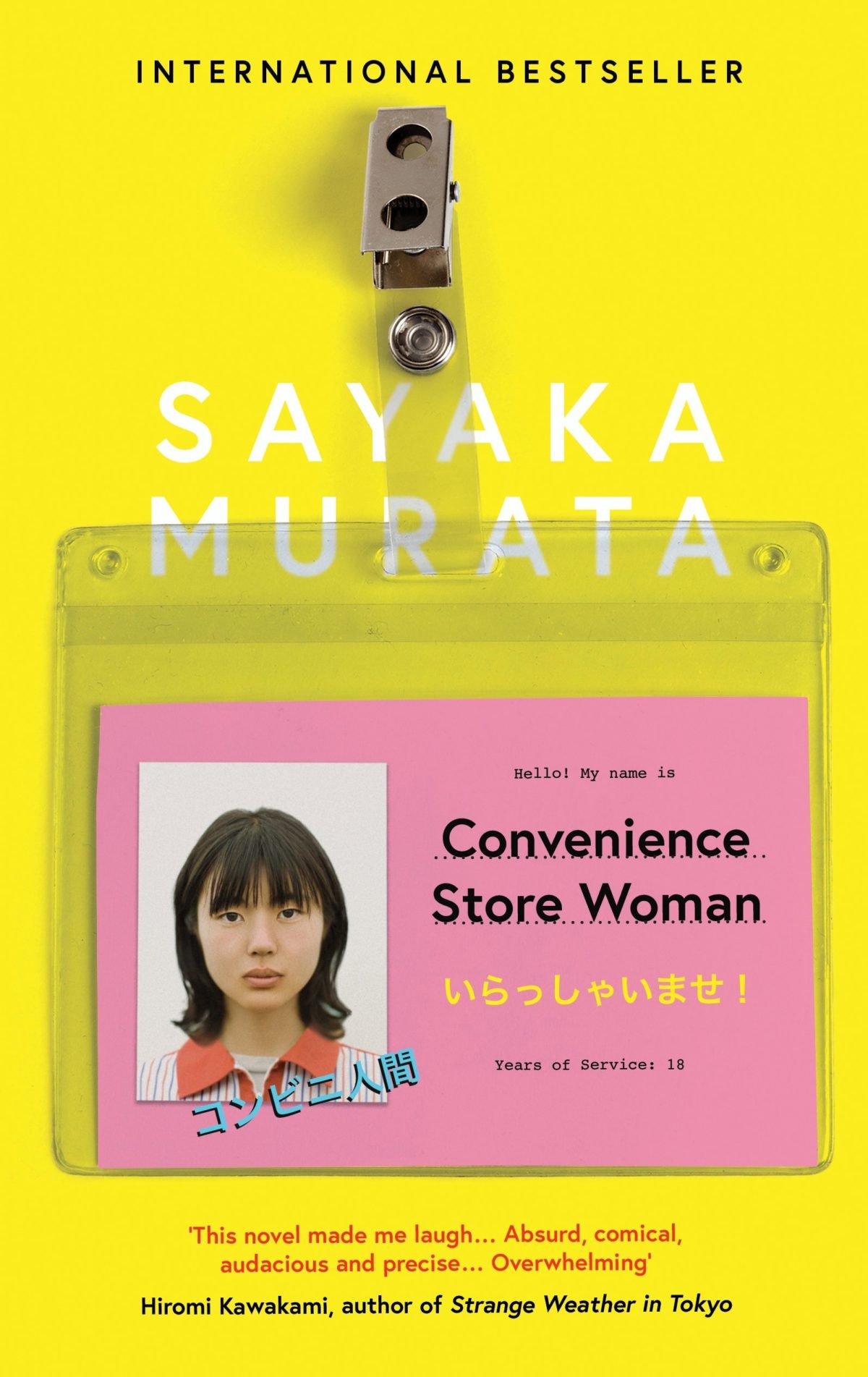

While virtually unknown to a Western audience, Sayaka Murata has become a well-respected author in her home country, winning multiple literary prizes, including most recently becoming a recipient of the Akutagawa Prize in 2016, as well as selling 600,000 copies for Convenience Store Woman alone. Serving as her first English-translated novel, Convenience Store Woman tells the story of a 36-year old convenience store worker, Keiko Furukura. Having spent 18 years working in a convenience store with no ambitions of pursuing another career or finding any romantic partners, Keiko is viewed as an outsider among her circle of friends, family, and coworkers.

Keiko is an enigmatic person, almost alien-like, as she displays a mimicry of others around her (speaking, dressing, and acting based off her coworkers), living outside the boundaries of social norms, but pretending to others as if she isn’t. In actuality, her view of the world treats the convenience store as the epicenter–all her thoughts, energy, and dreams gravitating to her workplace. She expresses ecstasy from the moment she greets customers in the morning, exclaiming, “I love this moment. It feels like ‘morning’ itself is being loaded into me. The tinkle of the door chime as a customer comes in sounds like church bells to my ears. When I open the door, the brightly lit box awaits me–a dependable, normal world that keeps turning. I have faith in the world inside the light-filled box.” The way she describes and articulates herself comes off as an extraterrestrial expressing thought and desire–something Keiko is almost aware of when she thinks about how she feels in the world outside the convenience store: “The normal world has no room for exceptions and always quietly eliminates foreign objects. Anyone who is lacking is disposed of.” Keiko’s alienation showcases the inconveniences of social expectations and constructs. Keiko’s only desires are to stick to the routine of the convenience store, as she’s already familiar with it–questioning why anyone thinks it’s strange why she doesn’t move on from that job. Even when she goes through a fraudulent relationship with an ex-coworker, which results in herself being recognized as a normal member of her social circles, she ends up coming to terms with that fact that her place in this world is to serve in a convenience store.The novel is a beautiful exploration of defying normality.

Similar Reads:The Memory Police by Yoko OgawaEvil and the Mask by Fuminori Nakamura

Me by Tomoyuki Hoshino