by Public Service Associate Owen

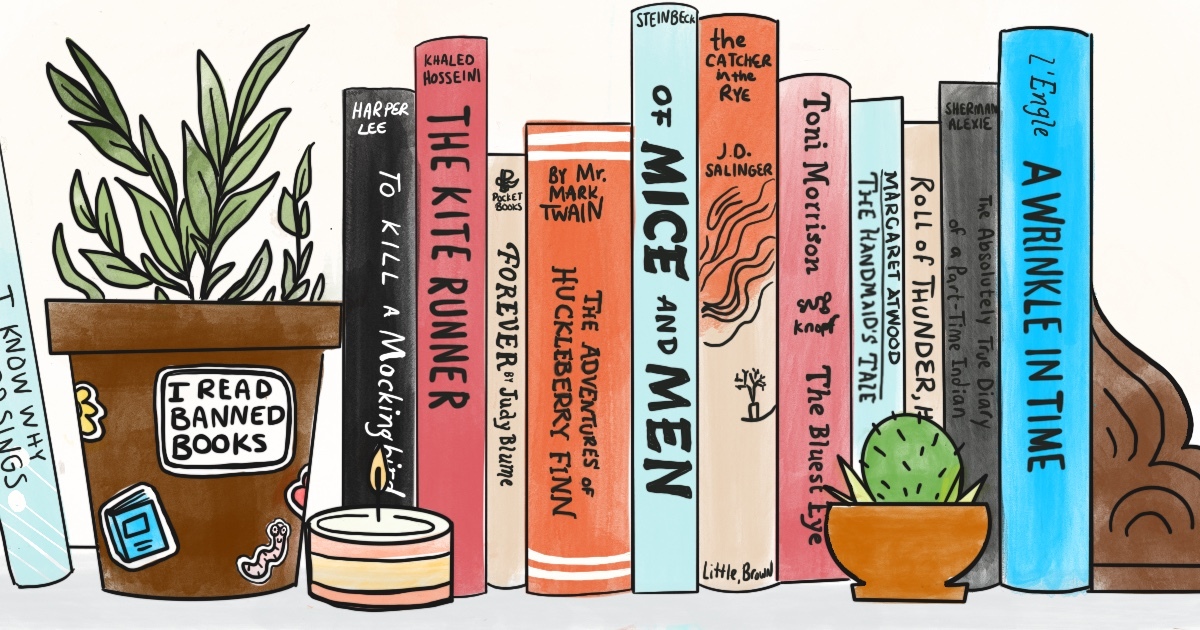

Yesterday marked the beginning of Banned Books Week, a week that aims to celebrate the freedom of literary expression. Book censorship is a rising problem in the United States, with the American Library Association reporting an “unprecedented” number of book challenges, as well as The New York Times dictating in January that “parents, activists, school board officials and lawmakers around the country are challenging books at a pace not seen in decades.” For whatever the reason, there has been a consistent rise in censorship attempts; Banned Books Week is an effort to both raise awareness in opposition to these attacks on literary freedom and to celebrate the books that have been targeted. I hope to lay out a brief history of book censorship, especially in the United States, to provide context as to why this week is so critical.

From the first cuneiform tablets and hieroglyph-laden papyrus scrolls, there has hummed a consistent desire from those of authority, for a myriad of reasons, to censor books and texts. Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of a united China, undertook book burnings in the 200s B.C.E. as part of an attempt to purge Confucian intellectuals. Catholic authorities heavily censored early Protestant texts in the 1500s to try and counter the blossoming Reformation. The German Student Union under the Nazi regime facilitated public burnings of books written by Jews, communists, liberals, anarchists, and anyone else who wrote works antithetical to their ideology. These are but a few examples from world history that show that book censorship – especially in its most extreme forms – is not a new phenomenon, is not specific to any one people or culture, and is executed for a variety of reasons.

As much as we extoll liberties such as freedom of speech and freedom of the press, book censorship has a long history in this country; censorship in the United States actually predates the founding of the country. In 1650, William Pynchon (coincidentally the founder of Springfield, Massachusetts) had his pamphlet The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption burned by the Puritan authorities of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, marking what is believed to be the first instance of book censorship in America. As the Thirteen Colonies grew, so too did censorship by the British authorities. In the 1730s books and pamphlets that espoused political dissent were suppressed, and any text that critiqued public officials was punishable by law as libel. These measures seem incredulous today, but they display the threat the written word possesses for those who oppose a freer, fairer society.

Following the founding of the United States, the federal government largely sought to distance itself from censorship, but this does not mean that it was not widespread as the new nation expanded. As the nascent nation found its footing in the nineteenth century, clear divisions still remained between the states. As a result, censorship was largely the initiative of state authorities, rather than the federal government. A book published in Rhode Island might have been banned in South Carolina, and vice versa.

As the issue of slavery neared a boiling point towards the middle of the century, abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in 1851 and sought to expose the heinousness of the practice. Slaveholders and authorities in slave states burned and banned the book; a minister named Sam Green was sentenced to 10 years in a Maryland penitentiary just for owning a copy of the book. Likewise, Mark Twain’s famous work Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was almost instantly challenged following its publication for its offensive language and portrayal of Black characters. It remains a controversial book to this day, and it continues to be one of the most censored and banned books in the nation’s history.

The Comstock Laws of 1873 brought the federal government back in the business of censorship. They deemed that it was illegal for erotica, sexually-explicit materials (including personal letters), and texts pertaining to contraceptives and abortions to be sent via the Postal Service. This was part of a larger censorship movement that lasted through the 1920s that aimed to be rid of any written materials that were deemed “obscene” or “immoral.” This law was eventually phased out, but it goes to show that even the federal government, which promises to protect our inherent freedom of speech, was at times in our history guilty of infringing on those very rights.

As the country moved into the mid-twentieth century, schools and libraries increasingly became battlegrounds in the fights for and against censorship. Even as the country grew to be more socially-liberal compared to its past, there remained a debate between parents, school administrators, library boards, and others to determine which books should and should not be readily-accessible. In schools, this came to a head when the Supreme Court protected students’ and teachers’ rights to freedom of speech in public schools in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), as well as prohibited the ability of school boards to remove books from school libraries simply because they did not agree with their contents in Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982).

Despite these protections in place, libraries came under the threat of so many book challenges and attempted book bans that Banned Book Week was created in the 1980s to help quell the tide of book challenges and to raise awareness against the threat of censorship. Despite these efforts, or perhaps because of these efforts, book challenges continue to rise. PEN America, a non-profit organization that advocates for free speech, reports that state legislators are passing “educational gag orders, proposals to track and monitor teachers, and mechanisms to facilitate book banning in school districts,” while “at the same time, the scale and force of book banning in local communities is escalating dramatically.” As the country continues to move in a more divisive direction, those who wish to impose restrictions on what can and cannot be read freely will become more active in their censorship efforts.

It is why the fight against censorship is still so critical, even as we move into an age of abundantly-available information. With book challenges and book bans rising by the year, it is more important than ever to recognize the value in texts that some deem should not be accessible.

Further reading:

- Attack of the Black Rectangles by Amy Sarig King | print

- Books Under Fire: A Hit List of Banned and Challenged Children’s Books by Pat R. Scales | print

- Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi | print / digital