by Programming Librarian Zach Parish

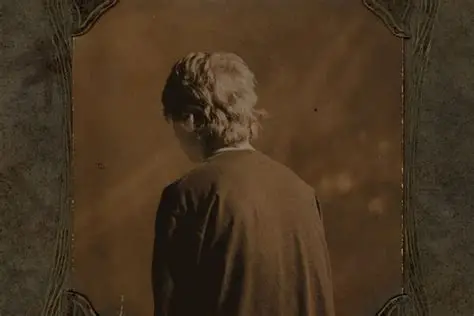

February 18th is Toni Morrison’s birthday and is officially recognized as Toni Morrison Day in Ohio. This year marks what would have been Toni Morrison’s 95th birthday and is being commemorated with a year-long, statewide celebration led by Literary Cleveland with Ohio Humanities, Ohioana Library, and the Toni Morrison Society. Beloved. Ohio Celebrates Toni Morrison officially kicks off on Wednesday, February 18, 2026, with a conversation between Namwali Serpell, author of the book On Morrison, and Hanif Abdurraqib held at The Columbus Foundation and available to attend via livestream.

Every February I return to a Morrison book that I’m moved to revisit for any number of reasons or choose one that has spent far too much time in my ever-growing TBR stack. Morrison’s work is always relevant but I enjoy the ritual of dedicating my February reading, when the late winter weather in Ohio all but demands me to seek refuge in a book, to something that requires self-contemplation and has the power to disarm, rearrange, and deliver me transformed into the new spring season.

Last year I picked up Beloved for the fourth or fifth time, its spine and pages beginning to show their wear, but my first time as a parent and it felt as if I was meeting Sethe and Denver for the first time. Reading one of Morrison’s most remembered passages from Beloved, “She is a friend of my mind. She gather me, man. The pieces I am, she gather them and give them back to me in all the right order.” I thought once again how this passage captures the transformative power of Morrison’s work, where the reader comes away with a few more truths unlocked and pieces of themselves rearranged for the better.

This year I am picking up Song of Solomon for the first time, one that has silently judged me from the top of my TBR stack for too long, motivated by the looming February BPL Book Club discussion.

I’m also returning to the all too relevant 2017 documentary, The Foreigner’s Home, that reflects on Morrison’s guest-curated 2006 exhibit at the Louvre. The documentary serves as a meditation on what it means to be a foreigner, remembering one’s own home in memory and ancestry and seeking a new home in belonging and citizenship, and challenges us to consider how we, as people and as a society, react to being, fearing, or accommodating the stranger.

The film also serves as a celebration of art and a call to arms for those who create, with Morrison stating, “The mission of art is the destruction of barriers and walls, things that prevent people from connecting, with their home or with each other.” It is with this spirit that we hope to bring people together and build community through celebrating Toni Morrison’s art and legacy with a suite of programs at the Bexley Public Library this month:

- 2026 Toni Morrison Celebration: Celebrating the Life, Words, and Legacy of Toni Morrison on Sunday, February 15 from 1:30 – 4:45 PM

- BPL Book Club – Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison on Monday, February 16 at 7:00 PM

- AARP Coffee Shop Conversation – A Brain Health Birthday Party for Toni Morrison on Wednesday, February 18 at 1:00 PM

- Namwali Serpell Author Visit – On Morrison Discussion with Dionne Custer Edwards on Thursday, February 19 at 6:30 PM

“My faith in the world of art is not irrational and it’s not naive. Art invites us to take the journey from data to information to knowledge to wisdom. Artists make language, images, sounds to bear witness, to shape beauty, and to comprehend. My faith in their work exceeds my admiration for any other discourse. Such conversation with the public and among various genre of art and scholarship, this conversation is vital to our understanding of what it means to be human.”

Opening of The Foreigner’s Home – Toni Morrison at the Louvre, 2006